“Cesspools,” Springs, and Snaking Pipes

Technology’s Stories v. 7, no. 1 – DOI: 10.15763/jou.ts.2019.03.13.02

The Hot Springs of Arkansas emerge from the hillside of Hot Springs Mountain, in the Ouachita Mountains about an hour’s drive from Little Rock. Although visitors today can only see a couple of “demonstration springs,” there once were 47 naturally occurring springs on the hillside. The waters emerge from more than 6000 feet below the surface, percolate up through faults in the shale and novaculite, and pool on the hillside.[1]

Hot Springs National Park is an odd little park, a site valued perhaps more for its history than the natural features that prompted its protection. Once, visitors flocked to the hot springs, seeking healing in the waters. At first, they did so simply by sinking themselves bodily into the springs. Before long, however, visitors, would-be landowners, and government officials began to use technologies to control the landscape—building bathhouses, installing pipes, and covering springs. By redirecting the water of Hot Springs, bathhouse owners and government officials controlled where and how water could be accessed for medicinal and recreational use. In the process, they altered the cultural landscape.

In addition to adding to the history of public lands and environmental health disparities, this story speaks to more current debates on these subjects. When we try to balance national park access with environmental impact, for example, do we consider who might be left out? When technology is—often justifiably—presented as serving the greater good, how do those choices shape and constrain access to public facilities? Taking a closer look at the social effects of technology at Hot Springs can offer broader insights into the social stakes of building infrastructures.

Hot Springs has a long history of attracting interest. European Americans who stumbled onto the springs found a region long used by indigenous peoples.[2] After the Quapaw ceded the land to the United States under an 1818 treaty, the area attracted health seekers hoping to find relief from a variety of ailments.[3] Interest in Hot Springs echoed a growing national interest in mineral springs and in hydropathy as a natural cure.[4] Drawn by its health benefits and sensing financial promise in the springs, Anglo-American settlers began claiming the land. Almost all hoped to control water access and charge for its use.[5] They implemented primitive technological interventions to make the springs more accessible and comfortable—and to help secure their claims. One of the earliest modifications was to dig around existing pools to make them larger. Others erected crude shacks or built sluices to redirect water from the hillside to more accessible structures below.[6]

To understand the value of the hot springs as a source of health, it is crucial to understand nineteenth-century perceptions of the connection between human bodies and nature. European-American settlers understood their bodies as permeable and intimately linked to nature as a source of both health and illness. Physically interacting with the environment—sitting in hot mineral springs, for example—was regarded as crucial to gain healing benefits.[7] These attitudes influenced not only the belief that the waters of Hot Springs could treat almost any illness, but also a sense that all Americans had a right to benefit from their existence.

Responding to the region’s popularity and the growing private control of the waters, the federal government intervened in these unauthorized claims to territorial land. In 1832, Congress declared an area called the Hot Springs Reserve under the purview of the Department of the Interior.[8] However, the vague language of the bill, and the lack of a federal representative in the region, meant that most people ignored the declaration.[9] For the next thirty years, residents continued to claim land. Buildings dotted the hillside, and the stream that flowed through the middle of town became a pit of open sewage. Rough pipes snaked across the landscape, carrying water from springs to locations downhill.[10]

In the early years of the Hot Springs Reserve, many visitors engaged directly with the water, slipping into hot pools alongside fellow bathers. Pools developed reputations as cures for specific ailments; the “Corn Hole,” for example, was so named because it was supposed to provide relief for foot corns and bunions.[11] Visitors came suffering from a variety of illnesses. One journalist described them as: “the gaunt, disjointed, becrutched cripples; the palsied and paralytic; the men and women with their flesh fairly flaming with scrofula and ulcers; bloated and blistered debauchees…men and women with every sort of disease, in every stage of progress, creeping, limping, and some of them even so helpless as to have to be carried to their baths–all come and are healed.”[12] Those who could not afford a place to stay camped on the hillside, living alongside the springs that they hoped would cure them.[13] An especially large group of these campers gathered around one pool, called “Ral Hole” because it was supposed to be helpful for neuralgia, probably caused by syphilis.[14] There, poor bathers sat alongside well-to-do sufferers on wooden planks.[15]

As the resort developed after the Civil War, the scene changed. More bathhouses were built, drawing clearer class lines as those who could afford them bathed under shelter, leaving indigent bathers on the hillside.[16] As Hot Springs drew more visitors, the government sought to enforce its ownership, and a legal battle over land claims persisted through the 1870s. A court settled the land issue in favor of the federal government in 1875, and 1877 legislation created the Hot Springs Commission to determine which lots of land could be sold.[17] The springs themselves were reserved by the federal government and rented for use by paid bathhouses.

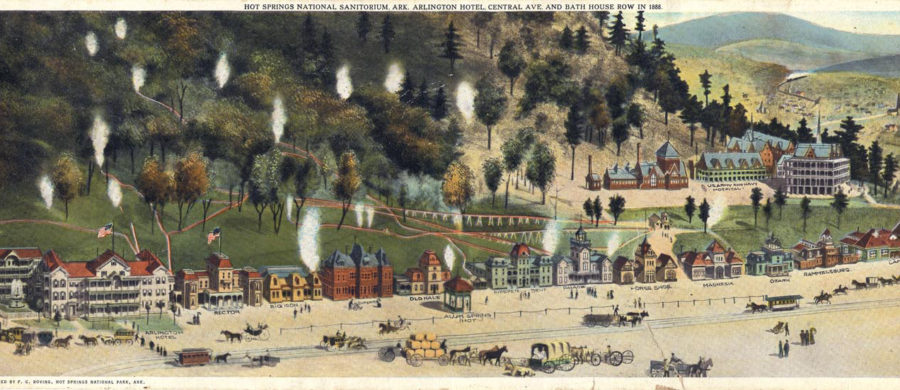

Figure 1. Men gathered around a building identified as the Government Free Bathhouse in 1877. However, the date on this photograph is either wrong, since the first Government Free Bathhouse was not established until 1879, or this is simply a rough building constructed over Ral Hole that is misidentified as a Government Free Bathhouse.

Courtesy of Hot Springs National Park Archive, Hot Springs, Arkansas

In taking control of the waters of Hot Springs, the government aimed to distribute the water more fairly and prevent any bathhouse from monopolizing the water or destroying some springs by enlarging others. When the bathhouse owners had controlled the pipes, some diverted more water than they could use and charged exorbitant rates.[18] If the federal government controlled the distribution, more people would be able to use the waters, and at a lower cost. These were worthy goals. The attempt to make access fairer for most, however, became fundamentally unfair for some.

With ownership of the water, the government moved to control the administration of Hot Springs. In 1877, the Department of the Interior appointed General Benjamin F. Kelley as the first superintendent of Hot Springs Reserve. In March 1878, a massive fire burned through Hot Springs, destroying many of the roughly constructed bathhouses and hotels.[19] Soon, the town began to rebuild, and federal officials and bathhouse owners took advantage of the fresh start. Officials determined where buildings could stand, resolving remaining property issues, and owners erected new, grand structures meant to draw a different class of people, those from the more moneyed classes who made a “season” of visiting health resorts for the twin purposes of resolving their pain and taking in the social scene.[20] The technological transformation of the hillside was poised to kick into high gear.

As the bathhouse owners envisioned a new resort future for Hot Springs, Ral Hole became a problem. Earlier, Kelley had tried to remove the indigent bathers from the mountainside to a separate facility, dubbed Kelleytown.[21] However, inferior technologies—pipes that allowed the water to cool and shoddily constructed buildings—meant that poor bathers had returned to the hillside. [22] Kelley fielded constant complaints from bathhouse owners about Ral Hole, Corn Hole, and Mud Hole, “the most filthy and offensive bathing places.” They gave multiple, sometimes contradictory, explanations for their concern. The indigent population wallowing in the pools, they said, polluted the water that ran down to the bathhouses, and “very many people after a survey of the situation, refuse to drink from any of the springs or bathe in the Water on account of the idea of contamination, and from these reasons alone, Hot Springs looses [sic] the patronage of thousands annually.” At the same time, they complained that these springs stole their customers, “people amply able to pay the small sum asked for baths at any of our bath houses.”[23] Regardless of the flaws in their logic, Kelley agreed and tore down the rough building over Ral Hole on September 25, 1878.[24]

Figure 2. Protestors reconstruct a structure near Ral Hole in 1878 following General B.F. Kelley’s orders to have all structures removed. Courtesy of Hot Springs National Park Archive, Hot Springs, Arkansas

The result was a protracted conflict, as indigent bathers refused to leave, staged protests, and made bathhouse owners fear that their buildings and lives were in danger.[25] One newspaper reported that a “mob surrounded the Grand Central Hotel and howled for Kelly…Threats have been made that they will burn down the town and lay the bath houses in ashes,” although in a letter to the editor, another person wrote that “although much regret was manifested, I heard no threats whatsoever.”[26] At Kelley’s request, an infantry division arrived in Hot Springs to bring order.[27]

Tellingly, one newspaper identified a key point in a later flare-up of the standoff: the troops, it said, were there not to protect the people or bathhouses, but “to protect the pipes leading from the Ral Hole into the Big Iron bath-house, threats having been made to the effect that the pipes were to be torn up and demolished.”[28] As pipes proliferated, they stood at the center of debates over who should access the springs and how they should be used. Pipes represented divides of class and race as they transformed the landscape to more sharply constrain who could access it.

The protesters crafted a petition, accusing Kelley of having “calculated to work a lasting injury to a large and worthy class of people.” They, too, embraced technology and suggested installing a drainage pipe to mitigate concerns about water pollution. They collected more than 500 signatures.[29] The petition drive, however, was unsuccessful, and the protest fizzled. Kelley had the Ral Hole pool filled in. However, over nearby Mud Hole, he allowed a small building for use by indigent bathers.[30] Congress acted, too. In December 1878, it passed legislation requiring Hot Spring Reservation to “provide and maintain a sufficient number of free baths for the use of the indigent.”[31]

In one sense, the protesters had won in their effort to defend their right to access nature. The law now codified access to health through the waters as a priority for Hot Springs. Still, just at the moment the rights of poor bathers were affirmed, the fight between indigent bathers and the wealthier residents transformed the environment of Hot Springs. The small wooden shack became the first Government Free Bathhouse on Hot Springs Reservation, and the landscape underwent a fundamental technological intervention. Government officials “walled up and covered over” almost all of the open pools on the hillside to prevent pollution.[32] The hot springs existed for the benefit of all, but now the water was confined to buildings and pipes. Never again would visitors be able to take their place in “a few inches of hot water and a foot or more of hot mud.”[33]

Figure 3: The Government Free Bathhouse in 1896, situated slightly behind the other grand structures on Bathhouse Row. Courtesy of Hot Springs National Park Archive, Hot Springs, Arkansas

Even with these environmental interventions, however, the use of technology in Hot Springs was contested. In keeping with beliefs about the connection between nature and bodies, bathers felt that the farther the mineral waters traveled to reach a bath, the less effective they would be. As one local doctor said, “the water in the Ral Hole and Mud Hole is undoubtedly better for bathing; as it is used just as it emerges from the earth, and loses none of its power by being conducted through pipes.”[34] With these perceptions, the free bathhouse, built directly over the Mud Hole, would have been healthier than the fancier bathhouses down the hill, where water was piped into the tubs. As a result, rich and poor bathed together at that early government free bathhouse.[35]

Over time, changing beliefs about public health and a new focus on sanitation meant that patrons worried less about their proximity to nature.[36] For the most part, those who could afford to had moved to the pay-bathhouses.[37] In 1911, access to free baths in Hot Springs was restricted further. To curb overuse of the free bathhouse and give in to pressure from paid bathhouse owners who thought potential customers might be abusing the system, Congress passed a law demanding that those who wanted free baths swear an oath that they could not afford to pay. If they were caught lying about their financial status, they faced a misdemeanor charge and a $25 fine or six days in jail.[38] In other words, the government still felt that the waters should be available to everyone, but with technology that restricted where people could access the water, they drew tighter boundaries around who could use the waters for free.

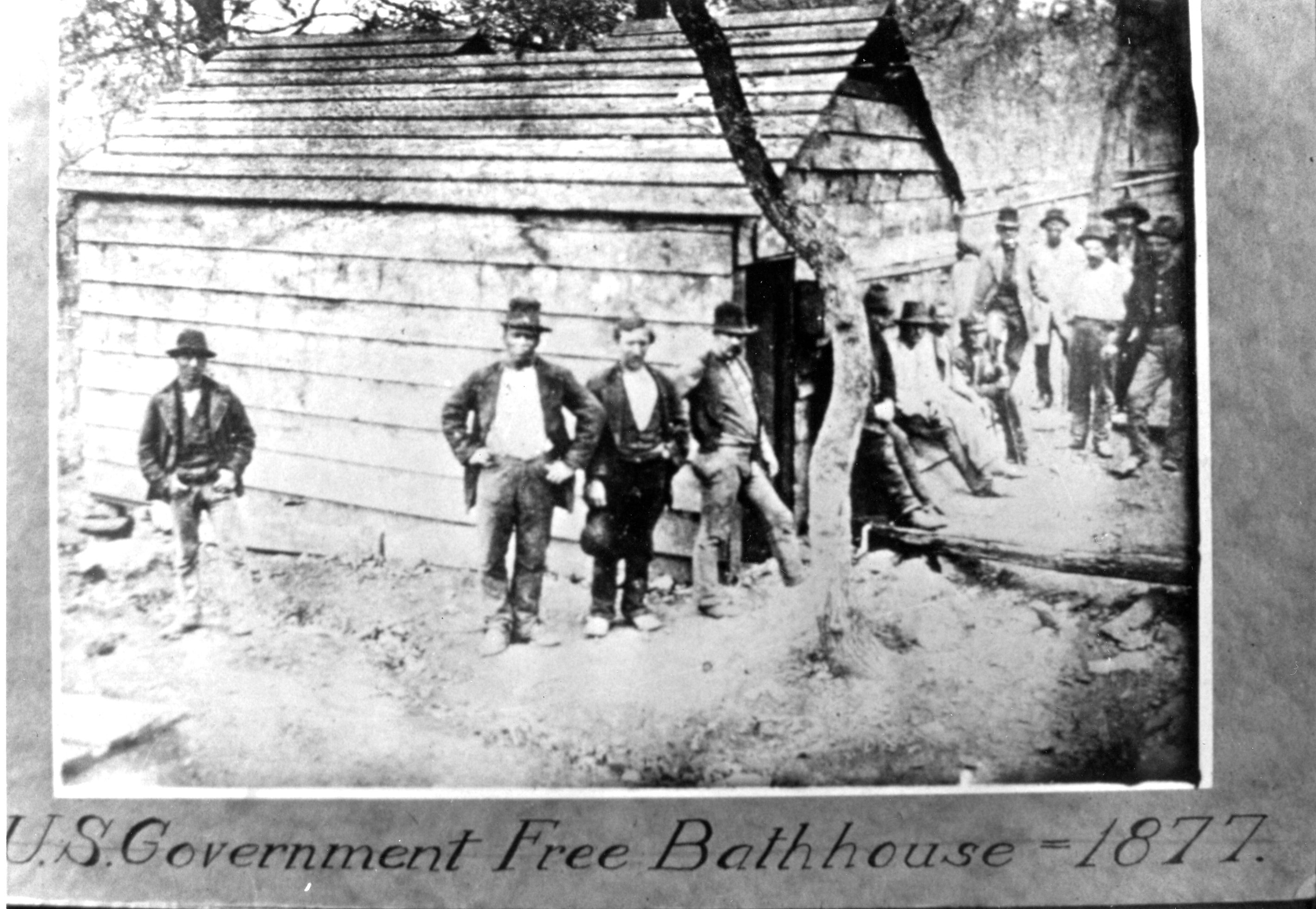

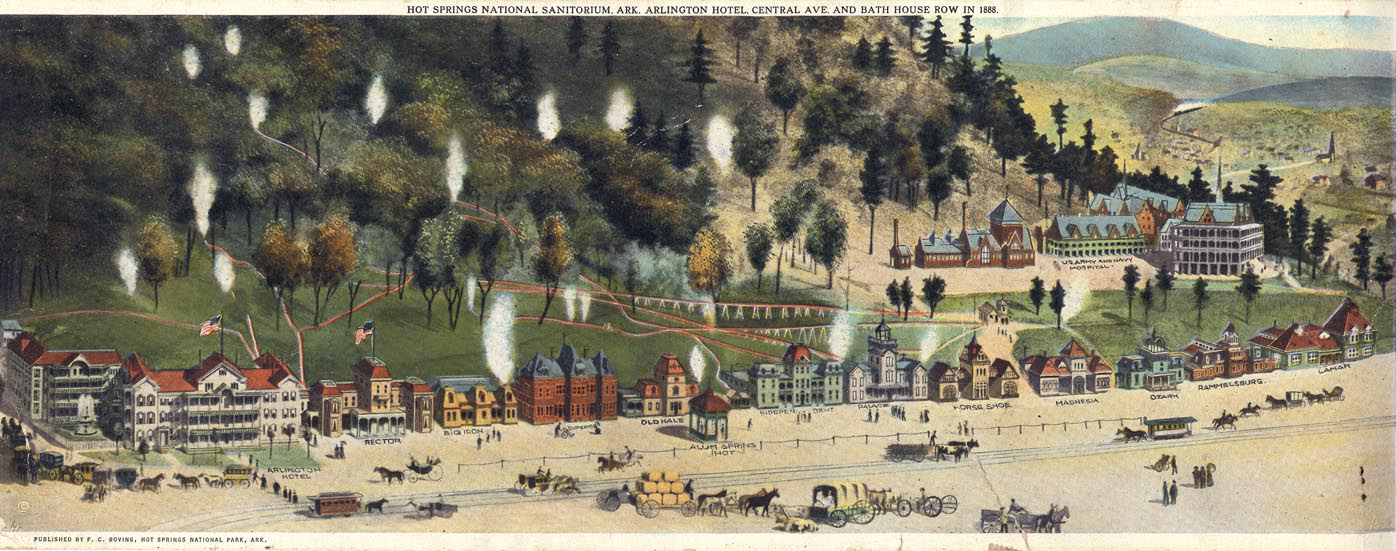

Figure 4: In this illustrated 1888 panorama of Hot Springs Reservation, the grand bathhouses stand in a row lining the street. The Government Free Bathhouse is situated just behind them on the right side of the image, the tiny building (here exaggeratedly small) between Bathhouse Row and the U.S. Army and Navy Hospital. Pipes and troughs carrying water to the bathhouses are also illustrated, and the clouds of steam represent places where naturally occurring springs once emerged from the ground but are now covered. Courtesy of Hot Springs National Park Archive, Hot Springs, Arkansas

Under the new law, visitors were forced to fill out a form stating their financial condition, listing any property they owned and their employment status, and stating their need for medical treatment. They answered interview questions from a bathhouse employee and swore their statement before a notary. The numbers at the free bathhouse dropped immediately, with 63,000 fewer baths given in 1912 than 1911. Officials took this as proof that the measure was effectively driving off people who had been able to afford baths all along.[39] This was probably true, but it is also possible that many free bathhouse attendees were uncomfortable with this extra level of scrutiny.

When officials believed that an applicant had lied, they investigated the person’s financial status. It is a little unclear how officials determined that someone might be lying; at least some perjurers were turned in by fellow bathers, and others were identified by people who encountered them in town and knew they had more money than they had claimed.[40] After catching someone in a lie, officials denied the patron access to the bathhouse, charged them with a misdemeanor, and fined them $25. If they could not pay, they spent a few days in jail instead.

The use of technology to restrict access to the waters also had implications for race. In the pools on the hillside, sick people of all races had bathed together. Within most bathhouses, however, owners limited use to whites. The free bathhouse allowed both white and black bathers—in fact, it was not segregated until several remodels later—and eventually, a paid bathhouse for African-American bathers was built off of the hillside. For at least a year in 1913, when that bathhouse had burned down, the only way an African-American could benefit from the waters of Hot Springs was to be poor enough to qualify for the free bathhouse or to perjure him or herself to get in.[41]

The changes at the free bathhouse took place against the backdrop of a growing Hot Springs Reservation. The Government Free Bathhouse, situated just behind the increasingly grand structures on Bathhouse Row, seemed like an aberration. In 1916, the federal government created the National Park Service, and Hot Springs Reservation came under its purview. As new officials took a more active role in management, Hot Springs leaders sought to improve on their resort-town dream. They pushed for more landscaping, improved walking paths, and other aesthetic improvements. Among these requests was the removal of the free bathhouse.[42]

Figure 5: The last iteration of the Government Free Bathhouse, constructed off of Hot Springs Mountain and away from Bathhouse Row in 1921. Courtesy of Hot Springs National Park Archive, Hot Springs, Arkansas

Before long, they got their way. With the influence of National Park Service director Stephen Mather, a larger, modern free bathhouse was under construction a couple of years later. It would not be on the hillside but situated a bit south and east of Bathhouse Row, not far from where Kelleytown had once stood. As before, water was piped to the facility, but now technology had improved so the water stayed hot. Publicity focused on the building’s state-of-the-art facilities. With pristine tile, porcelain tubs, and ample space for a medical clinic, the new free bathhouse was described by one newspaper as “the most advanced thing that any nation has constructed for its afflicted poor.”[43] These attributes reflected changing medical beliefs, including an emphasis on bacteria and sanitation, rather than natural environments, as sources of disease and health. Perhaps these changes are why the clients of the free bathhouse do not seem to have protested the move away from the source of the springs.With the landscape transformed by technologies and more tightly controlled as a resort environment, perhaps they also felt fortunate to have a place to bathe at all.

By the early 1920s, the vision for Hot Springs prioritized its function as a profitable resort. The nineteenth-century emphasis on the connection between body and nature had largely given way to new beliefs about bacteria as the cause of disease, so sanitary facilities were more important than proximity to nature. Still, even before these changing beliefs, technology had played a pivotal role in enabling this wholesale transformation of the way officials and visitors understood the landscape of Hot Springs. Once all water had been routed through pipes, holding tanks, and bathhouses, it was easier to dictate who could access the water and how they should use it. Visitors no longer sank into pools on the hillside, regardless of race or class. With each subsequent restriction on free baths, the number of indigent bathers using the free bathhouse dropped. Technology might have enabled more people to use the water, but it kept some people from being able to use it at all.

Figure 6: A 2017 photograph on Bathhouse Row at Hot Springs National Park. The bathhouse in the foreground now houses the park’s visitor center. Photograph provided by author.

Kathryn Carpenter is a graduate student in the Public History program at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Copyright 2019 Kathryn Carpenter

Notes

[1] Jeffrey S. Hanor, Fire in Folded Rocks: Geology of Hot Springs National Park. (Hot Springs National Park: National Park Service, 1980).

This research was supported by the UMKC Women’s Council through the Linda Herner Barrick-Kansas City Young Matrons Award, Friends of Mary Merryman Award, and the Corky and Bill Pfeiffer Award in honor of the Art & Art History Department.

[2] There is little historical evidence to support a local myth that the springs were a place of peace that warring tribes declared a neutral zone, but archaeological evidence does suggest that indigenous residents likely used the springs.

[3] Janis Kent Percefull, Ouachita Springs Region: A Curiosity of Nature. (Hot Springs, Ark.: Ouachita Springs Region Historical Research Center, 2007).

[4] This interest among Euro-Americans was by and large imported from Europe. For far more on European mineral spas and hydropathy see The Great American Water-Cure Craze: A History of Hydropathy in the United States, by Harry Weiss (Trenton: The Past Times Press, 1967), and James C. Whorton’s Nature Cures: The History of Alternative Medicine in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

[5] Percefull, Ouachita Springs Region.

[6] Frederick W. Cron, “The Hot Springs of Ouachita,” unpublished manuscript, 1938. Frederick Cron Collection, Box 1, Garland County Historical Society. Pp. 168-169.

[7] For more on the subject of nineeenth-century beliefs about health and the environment, see Linda Nash, Inescapable Ecologies: A History of Environment, Disease, and Knowledge. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006); Conevery Bolton Valenčius, The Health of the Country: How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land. (New York: Basic Books, 2002); and Gregg Mitman, “In Search of Health: Landscape and Disease,” Environmental History 10, no. 2, April 2005, 184-210. Nash uses the word “permeable” to describe the perception of bodies, which I have borrowed here.

[8] Why exactly the federal government took such an interest in this land is unclear. The federal government had shown an interest in the Hot Springs area since the early nineteenth century, when Thomas Jefferson sent an expedition to explore the region in 1808. Arkansas representatives may have played a role. Territorial representative (and, after 1831, Congressional representative) Ambrose Sevier sponsored the initial legislation seeking to declare this area a reserve. It is unclear why he pushed for federal ownership.

[9] Act of Congress, Section 3, “An Act authorizing the governor of the territory of Arkansas…” 31st Congress, 1st Session, Senate, Ex. Doc. 70.

[10] Ron Cockrell, The Hot Springs of Arkansas—America’s First National Park: Administrative History of Hot Springs National Park. (Omaha, Neb.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service Midwest Regional Office, 2014). 40-42.

[11] A. Van Cleef, “The Hot Springs of Arkansas,” Harper’s Monthly, 1878, pp. 200-201.

[12] Curtis, “Baths and Potash,” Inter Ocean, December 12, 1874.

[13] “City and General Items,” Daily Arkansas Gazette. Little Rock, Ark., September 23, 1876.

[14] Sharon Shugart, “The Legacy of ‘Ral City’,” The Record, Garland County Historical Society, 2008, p. 64.

[15] “The Hot Springs Ral Hole: Secretary Schurz to be Interviewed Regarding its Abolishment.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 4, 1878.

[16] Cockrell, The Hot Springs of Arkansas, pp. 25-27.

[17] Report of the Commission Regarding the Hot Springs Reservation in the State of Arkansas. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1877).

[18] Ibid.

[19] Cockrell, The Hot Springs of Arkansas, pp. 33-34.

[20] Percefull, Ouachita Springs Region, 60, and Cockrell, The Hot Springs of Arkansas, 34.

[21] Annual Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior for the year 1878, Superintendent B.F. Kelley to Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz. November 14, 1878.

[22] “A ‘Tall’ Speech Before the Congressional Committee on Hot Springs Legislation,” Hot Springs Daily News, December 31, 1884.

[23] Bathhouse Owners to Carl Schurz, Secretary of the Interior, August 6, 1878; Box 3, Hot Springs General Correspondence (1877-78), Folder 1; Letters Received by the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Related to National Parks, 1872-1907; Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Related to National Parks, 1872-1907; Records of the National Park Service, Record Group 79; National Archives Building at College Park, MD.

[24] General B.F. Kelley to Carl Schurz, Secretary of the Interior, September 28, 1878; Box 3, Hot Springs General Correspondence (1877-78), Folder 1; Letters Received by the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Related to National Parks, 1872-1907; Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Related to National Parks, 1872-1907; Records of the National Park Service, Record Group 79; National Archives Building at College Park, MD.

[25] “Hot Work at Hot Springs,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 27, 1878.

[26] “Hot Work at Hot Springs,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 27, 1878; “A Protest Against the Monopoly of the ‘Ral Hole’,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 4, 1879.

[27] Kelley to Schurz, September 28, 1878.

[28] “Spray From the Springs,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 29, 1879.

[29] Petition to Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz, September 30, 1878. Box 13, Hot Springs General Correspondence (1892-93); Letters Received by the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Related to National Parks, 1872-1907; Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Related to National Parks, 1872-1907; Records of the National Park Service, Record Group 79; National Archives Building at College Park, MD.

[30] Report from J.B. Clark to Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz, June 12, 1879 Box 4, Hot Springs General Correspondence (1879-1881), Folder 1; Letters Received by the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Related to National Parks, 1872-1907; Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Related to National Parks, 1872-1907; Records of the National Park Service, Record Group 79; National Archives Building at College Park, MD.

[31] Act of Congress, December 16, 1878 (20 Stat. 258).

[32] Cockrell, The Hot Springs of Arkansas, 61.

[33] Curtis, “Baths and Potash,” Chicago Inter Ocean, December 12, 1874.

[34] Dr. F. Hartmann to Carl Schurz, Secretary of the Interior, October 1, 1878; Box 3, Hot Springs General Correspondence (1877-78), Folder 1; Letters Received by the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Related to National Parks, 1872-1907; Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Related to National Parks, 1872-1907; Records of the National Park Service, Record Group 79; National Archives Building at College Park, MD.

[35] Clark to Schurz, June 12, 1879.

[36] By 1893, the free bathhouse was supposed to be exclusively for the use of indigent bathers. At that point, though, this was just a rule, not a law, and there were limited ways of enforcing it.

[37] Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1895. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1895). Hot Springs National Park Archive, Hot Springs, AR.

[38] Act of Congress, 2 March 1911, (36 Stat. 1015).

[39] Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1912. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1912). Hot Springs National Park Archive, Hot Springs, AR.

[40] See, for example, letter from “Citizen” to Superintendent C.R. Trowbridge, January 4, 1914; Folder C3323, Concession Administration: Government Free Bathhouse, 1913-1931; Hot Springs National Park Archive, Hot Springs, AR.

[41] “African Americans and the Hot Springs Baths.” (Hot Springs National Park, Ark.: National Park Service, date unknown.)

[42] Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1916. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1916). Hot Springs National Park Archive, Hot Springs, AR.

[43] “Free Bath House Formally Opened,” Arkansas Gazette, November 15, 1921.