Dreamscapes of Accelerated Development: Uses and Abuses of Artist Impressions in John L. Savage’s Yangtze Gorges Proposal, 1944-1946

Technology’s Stories v. 8, no. 1 – DOI: 10.15763/jou.ts.2020.06.08.03

In the fall of 1944, John Lucian Savage, the American dam builder from the Bureau of Reclamation, arrived in China to survey the Yangtze Gorges. After cursory surveys upstream from the proposed site of the dam, Savage drafted a report proposing the construction of a dam 738 feet high straddling the Yangtze River at Yichang, Hunan Province. The massive amount of water would power 96 mighty generators and produce five times more electricity than the Grand Coulee Dam, which was then the highest in the world. Savage did not specify the amount of time taken to complete the project. This oft-quoted passage from Savage’s “Excerpts from Preliminary Report on Yangtze Gorges Project, Chungking, China” sums up the promise of accelerated development associated with massive integrative river basin development:

The Yangtze Gorge Project is a “CLASSIC.” It will be of utmost importance to China. It will bring great industrial developments in Central and Western China. It will bring widespread employment. It will bring high standards of living. It will change China from a weak to a strong nation.[1]

How did Savage promote his vision of accelerated development to an American audience? What is the role of aesthetics in Savage’s overall rhetorical strategy? This article draws on a collection of newspaper clippings and photographs filed away in John Lucian Savage papers at the American Heritage Center at Laramie, Wyoming and the files pertaining to the Yangtze Gorges Survey at the National Archives and Records Administration office at Bloomfield, Colorado. These sources suggest that Savage approached the Upper Yangtze with blank-slate mindset by not taking into account the local complexities. Savage’s Yangtze Gorges survey should be treated as a story about the hazards of the top-down approach to economic developmentalism, which according to economist William Easterly, in which each poor society is seen as “infinitely malleable for the development expert to apply his technical solutions.”[2]

The Three Gorges Dam is one of the most extensively studied hydropower project in the history of technology. William Jones and Marsha Freeman’s article “Three Gorges Dam: The TVA on the Yangtze River” (2000), along with David Ekbladh’s The Great American Mission (2011) and more recently Christopher Sneddon’s Concrete Revolution (2015), have adequately covered the connection between the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Three Gorges Dam project. The epigraph of the Jones and Freeman article cites China historian John King Fairbank saying in 1948 that “TVA makes sense in China. The use of public funds for big public works and water control, the government and individual citizen cooperating in the application of modern technology to the ancient problems of the soil…-this is the most clear-cute democratic ideal in Asia.”[3] Existing scholarship has also treated Savage favorably praising him as a visionary whose grand developmental plans were interrupted by the war. The examination of the use of visual materials in the publicity of the Yangtze Gorges project reveals some of Savage’s problematic assumptions underlying Savage’s ideas.

One of the most commonly cited photographs of Savage’s survey of the Yangtze River features Savage looking at the banks of the Yangtze while traveling on a rowboat with three Chinese officials. This picture appears in an article titled “Billion Dollar Engineer” in the Rocky Mountain Magazine published on March 28, 1948. The caption describes Savage as an engineer with a “far-seeing mind” seeking to transform the “rampaging Yangtze river” with the “world’s largest “irrigation-power project.”[4] The article was published months after the Nationalist government in China shelved the Yangtze Gorges project. After describing Savage’s unwavering faith that the Yangtze Gorges project was still alive, Roscoe Fleming, who had previously interviewed Savage for an article in Popular Mechanics published in March 1946, offers a biographical sketch of Savage that provides important insights into what was going on in Savage’s mind when he sailed along the Yangtze just a few miles within Japanese lines. Savage graduated from the University of Wisconsin in 1903, the year after Congress authorized the establishment of the Bureau of Reclamation. He took up a teaching position at Purdue University when his initial application went unanswered. Savage ultimately received an offer from the Bureau of Reclamation and departed from the Snake River in Idaho to take on the budding Minidoka project. Savage told Roscoe Fleming, the author of the article, that when he first arrived at the Snake River Valley, it was “about as wild and desolate a spot as the U.S. affords. There were just two houses—the only signs of human habitation amidst millions of acres of sagebrush.” The desolate banks of Yangtze River, which have been emptied of its population, due to the fighting between Chinese and Japanese might have reminded him of his earlier experience in the Snake River Valley. Having little to no contact with the local population, Savage saw the Upper and Middle Yangtze as a blank slate for his project.

The description of the Yangtze Gorges project aimed at the American audience offers further proof of Savage’s blank-slate mentality. The first media blitz for the Yangtze project appeared around March 1945, as Savage was trying to convince the State Department to support the project. Savage helped the American readers visualize the project’s scale by comparing the proposed project to existing hydropower projects in the United States. “The Yangtze Dam Would Make the Boulder Look Like Mud Pie,” screams the headline of an article by Richard Strout from The Christian Science Monitor on March 13, 1945. In the first public press conference, Savage declared, “I don’t know of any possibility of a power plant of this magnitude on any other river of the world.” He estimated “conservatively” that the cost per kilowatt of power for the Yangtze Gorges would be US$39, which was extraordinarily cheap compared to the $115 per kilowatt of the Grand Coulee Dam. He even estimated dam construction would be completed in six to ten years, upon which twenty per cent of its projected capacity would be available.[5] In another article published in The New Republic on March 26, 1945, Richard Strout takes Savage’s mudpie analogy and pushes it one step further:

If you can imagine diverting the Mississippi River into the Grand Canyon, throwing a dam across the Grand Canyon, constructing gigantic developments that make Boulder Dam and Grand Coulee look like mudpies, and putting the whole affair in a teeming, energetic, hand-loom civilization that comprises 140 million people within a 300-mile radius, then you have a rough concept of the proposal that John Lucian Savage has brought back with him from China.[6]

Beneath the optimistic rhetoric, there were indications about the infeasibility of the Yangtze Gorges project. The accompanying visual to Strout’s March 1946 article in the Christian Science Monitor calls into question Savage’s projections. A photograph with the caption “Yangtze Gorge: A Hint of China’s Vast Hydropower Potential—“On the immense and turbulent Yangtze” sits beneath the optimistic headline. Looking at the picture, one might ask: How will the materials used to construct the dam be transported to the project site? How would a state that was still transporting its mail by boat shoulder such a massive undertaking? These questions were not addressed in the accompanying report. Savage, the “blue-eyed, slow-spoken, self-effacing” “billion dollar beaver” would use his expertise from constructing 10 billion dollars worth of dams to transform his blueprint into reality.

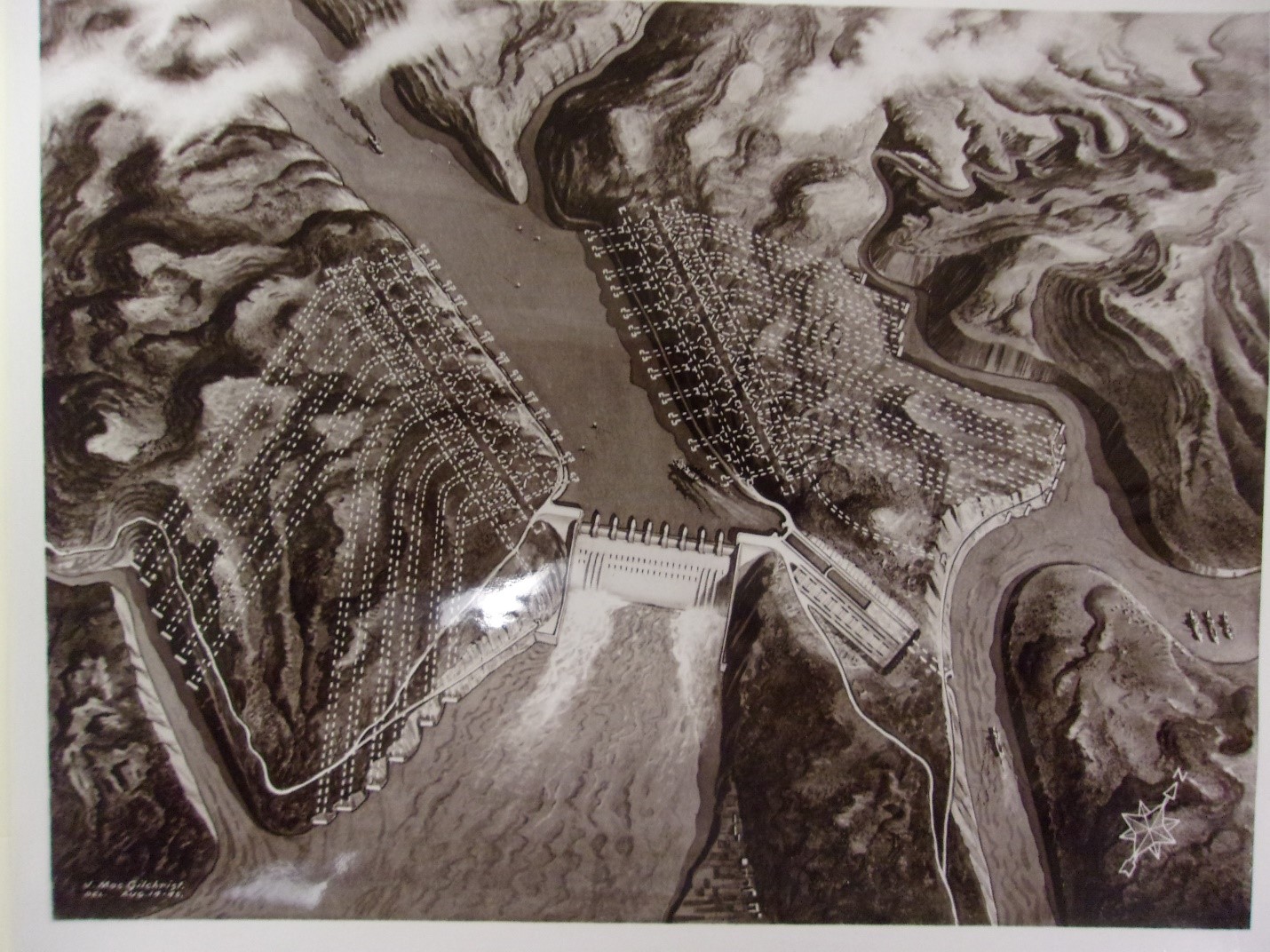

Impressive visuals of Savage’s proposed Yangtze Gorges Dam appeared in the media reports published in March 1946, right after Savage’s return to China upon the conclusion of the Sino-American cooperation agreement. These artist impressions appear like dreamscapes, depicting a future in which the Yangtze River thought to be “a mighty monster, who work for man one minute, then turns and devours him,” will be put in “chains” that are “forged in an office in Denver, Colorado.”[7] The landscape portrayed in these images appears differed significantly from the idyllic scenes described by observers who traveled along the Yangtze with Savage. The junks with sails made of matting that were purportedly “exactly like these sailed the Yangtze hundreds of years ago” [8] would be replaced by massive ocean steamers that could sail straight into the city of Chongqing in Southwest China, as they would be lifted 530 feet from the river to the reservoir behind the dam with eight massive ship cranes. The “little walled towns, each with a Buddhist temple” and “fishing nets strung on long poles sticking out from the banks” would be erased from the landscape. In their place stands Savage’s masterplan of a megadam straddling the Yangtze with dozens of diversionary tunnels running beneath the mountains that would channel vast amounts of water to run 96 generators.

Fig-1 Artist impression of John Lucian Savage’s proposed dam across the Yangtze. John Lucian Savage Papers, Box 4, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

A reservoir stretching back 250 miles from Yichang would displace hundreds of thousands of people living in the river valley. In Savage’s calculus, this was for the greater good of 140 million people who lived within the 300-mile radius and would benefit from the cheap hydropower. The iconic image of the project was supposed to fill the reader with awe. It served as a manifesto for China’s war against nature but offered few specifics on how to achieve the final objective.

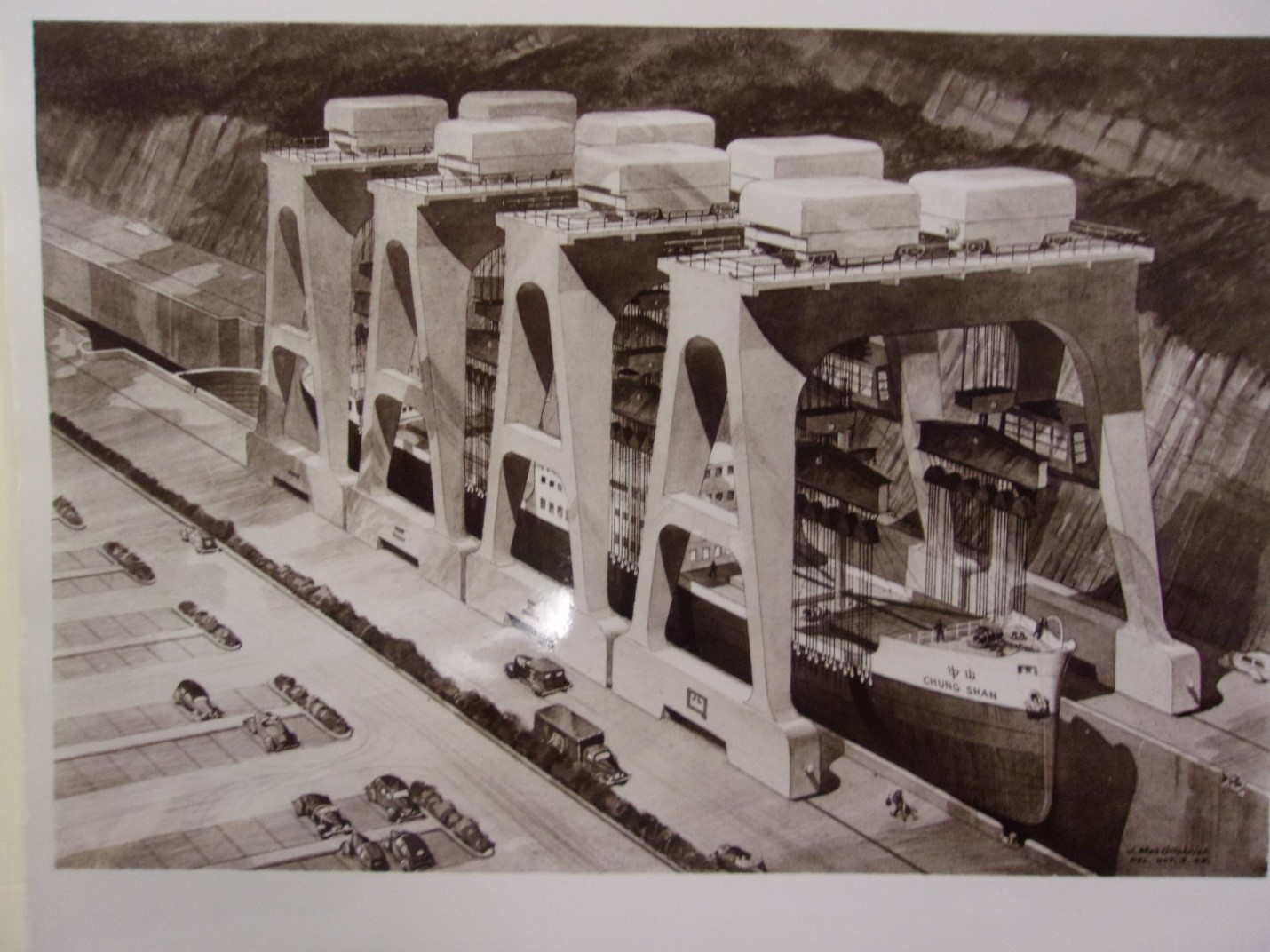

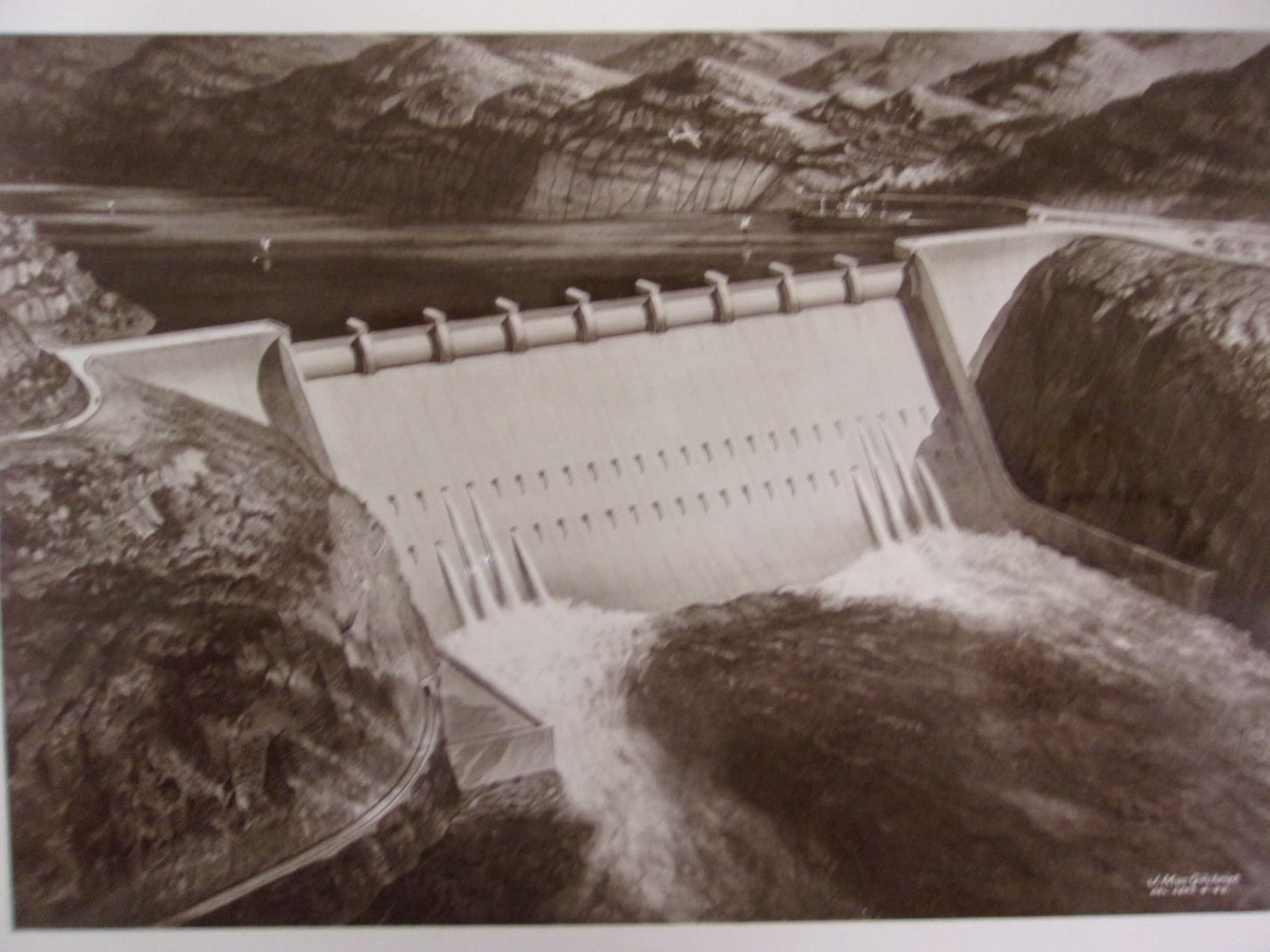

Looking at how the media used these images, it appears that the only story that mattered at that moment was the promise of Savage’s engineering feat. The Baltimore Sun report on March 3, 1946 for example, selected the image of ship cranes lifting ships past the dam and bombarded its readers with mind-boggling numbers of the project: The proposed dam was 24 feet higher the Grand Coulee, its mass of 15 million cubic yards was 50% larger than the Grand Coulee, it also detailed the 250 mile reservoir and the 10 million acres of land irrigated. The image served to help the readers grasp the massiveness of the project. The images of a rosy future drowned out any uncertainty conveyed through in the text. [9]The March 17, 1946 report on the New York Times titled “China Plans A Super TVA” begins on a tentative tone, stating that “Despite her internal difficulties China is looking hopefully to the future,” and hesitantly continues in the second paragraph with, “If the Yangtze is eventually harnessed, the project will be far larger than our Tennessee River development.”[10] Taking in only the headline and the image, the reader glosses over the nuanced complexities conveyed in the news article.

Visuals from the Yangtze Gorges Project were even used as a symbol of hope for Sino-American relations. In the March 1946 edition of Current Events, a side bar with the artist impression of the Yangtze Gorges Dam was inserted into a news story about the agreement signed by US General of the Army George Marshall, General Zhang Zhizhong of the Guomindang regime, and Zhou En-lai of the Communist regime, signed in “a Chungking office” as “floodlights flanked a wooden desk.” John Lucian Savage’s biography praising him of working out “a plan worthy of Superman,” appears on the opposite page, as if to suggest that the American master dam builder would bring about the turning point of China’s fortunes. Savage’s Yangtze Gorges proposal was easily considered an antidote to bad news coming out of a China that was descending into civil war.

Even after the termination of the Yangtze Gorges survey in August 1947, the artist impressions served as icons of accelerated development. A comparison of reports in March 1946 and August 1948 about Savage’s proposed dam written by Roscoe Fleming, a correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor and columnist for the Denver Post, reveals the staying power of these iconic images. Fleming’s March 1946 article in Popular Mechanics have employed the images to convey the two “daring scopes of the project,” namely the “boring of 20 great tunnels from the river bed into two nearby tributaries of the Yangtze” and the revolutionary ship cranes with which “ships will be raised or lowered the entire distance—more than twice the height of the Niagara—by just one lock, a wide ‘well’ 530 feet deep.”[11]

Fig 2. Artist impression of ship cranes that could hoist ocean liners and allow them to sail upstream to Chongqing. John Lucian Savage Papers, Box 4, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

Fleming used the iconic ship crane image in his August 1948 article and makes the point that the Yangtze Gorges project had been temporarily shelved and that Savage had never lost faith in the project that would create “a great, strong heart, pumping the lifeblood of electrical power, new industry and renewed agriculture into the veins of a revitalized China.”[12] Gone were the outrageous projections that the cost of Yangtze Gorges would be recouped in 20 years. Added to the article was an insistence that Savage was in no way an adventurer, for the word adventure connotes “bad planning.” It only appears that Savage simply transported his visions of accelerated development to four different integrative river basin development projects on four continents. After the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan in 1949, Savage would travel there in the 1950s to serve briefly as a consulting engineer for hydropower projects on the island.

Fig 3- Artist impression of the dam. This is the visual that accompanied the New York Times article with the headline “China Plans a Super TVA. John Lucian Savage Papers, Box 4, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

A critical reading of the images challenges the conventional narrative that describe Savage as a visionary who was ahead of his time and whose grand plans to lift the Chinese people out of poverty through the accelerated development of hydropower had fallen through due to political turmoil in China. A close reading of these visuals and their circulation in the media serves as a reminder of hyperbolic promises of top-down economic developmentalism. The absence of humans in the landscape or the treatment of human beings as a statistic is a warning sign of the possible human cost of such projects.

Copyright 2020 by Ying Jia Tan

Ying Jia Tan is Assistant Professor of History at Wesleyan University.

[1] J.L. Savage, “Excerpts from Preliminary Report on Yangtze Gorges Project, Chungking, China,” 12. Also cited in William C. Jones and Marsha Freeman, “Three Gorges Dam: The TVA on the Yangtze River,” 21st Century (Fall 2000) and Corey Byrnes, Fixing Landscape: A Techno-Poetic History of China’s Three Gorges Dam (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019).

[2] William Easterly, The Tyranny of Experts: Economists Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor (New York: Basic Books, 2014), Chapter 2.

[3] Jones and Freeman, 1.

[4] Roscoe Fleming, “The Billion Dollar Engineer,” March 28, 1948, Rocky Mountain Empire Magazine, 8.

[5] “Yangtze Dam Would Make Boulder Dam Look Like Mud Pie,” March 13, 1945, Christian Science Monitor; Accessed through RG 115, Yangtze Gorges Project (1943-1949), box 9, NARA (Denver).

[6] “Kilowatt for Lamps in China,” March 25, 1946, The New Republic. Accessed through RG 115, Yangtze Gorges Project (1943-1949), box 9, NARA (Denver).

[7] “Yangtze: How China Will Tame Her Mightiest Rivers,” March 1946, Current Events, 204-205. Accessed through John Lucian Savage Papers, Box 3, American Heritage Center, Laramie, Wyoming.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Chinese Planning Great Power Dam,” March 3, 1946, The Sun, Baltimore. Accessed through John Lucian Savage Papers, Box 3, American Heritage Center, Laramie, Wyoming.

[10] “China Plans a Super TVA,” March 17, 1946, The New York Times. Accessed through John Lucian Savage Papers, Box 3, American Heritage Center, Laramie, Wyoming.

[11] Roscoe Fleming, “Damming the Yangtze Gorge,” Popular Mechanics, March 1946, 102-103. Accessed through John Lucian Savage Papers, Box 3, American Heritage Center, Laramie, Wyoming.