Techno-Histories in Mozambique: A Photographic Story

Figure 1

Technology’s Stories vol. 3, no. 3 – doi: 10.15763/JOU.TS.2015.9.1.02

PDF: Thompson_Techno-Histories in Mozambique

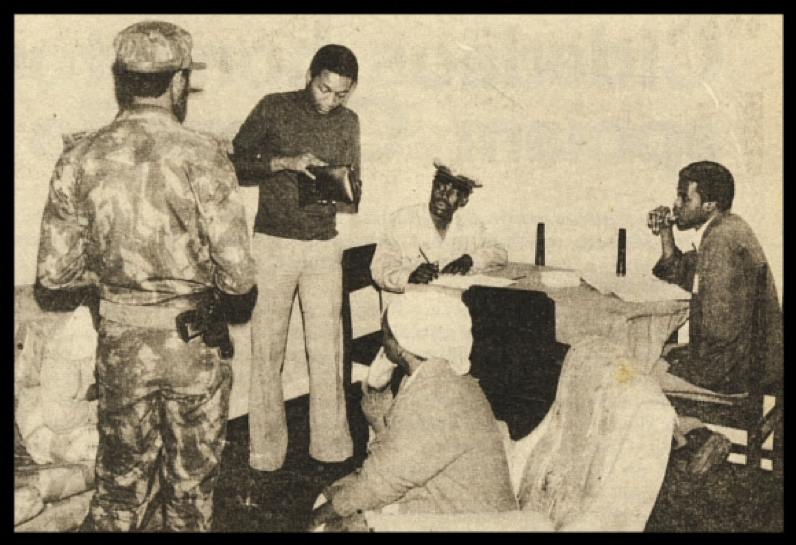

A person (Figure 1) dressed in fatigues has his back to the camera (that is photographing the scene) and stands in a living room. The pictured subjects (five of whom are in the frame) appear to direct their attention towards another male figure that stands in the frame slightly off center, revealing two figures with their pens and notebooks seated at a table. It should be noted that a person appears to be seated on the couch but the soldier blocks him from being viewed by the camera. None of the figures make eye contact with the camera but instead appear to be anticipating the man dressed in civilian clothes to reveal an undisclosed object from the wallet he holds. The picture in question is a digital copy of an original and includes the text, “A verification brigade including a policeman and a soldier checking residents’ documents house-by-house visits, July or August 1983.” The captions allows a viewer like myself to place the photograph at the center of the 1983 forced removal scheme in Mozambique known as Operation Production. As part of an effort to remove people from Mozambique’s overcrowded cities to under-producing rural areas, the state required individuals to carry a range of identity documents. An inability to produce these documents placed individuals at risk for forced removal, often against their will. This opening photograph is illustrative of what I am calling photography’s “techno-histories” and the representational politics that unfold around photography’s use. By “techno-histories” I am referring to the modes of representation and visualization embedded within photography, and the ways in which the use of multi-dimensional technologies like photography filter, trigger, and enact these modes of representation and visualization at different points in time.

Fast-forward more than 25 years after the date of Figure 1’s production. In 2010, the Frelimo party, which rose to power in 1975, introduced new identity documents that included the biometric tracking chip. The opening photograph challenges notions that comprehensive and innovative forms of popularly supported modes of surveillance did not exist in Mozambique before the introduction of the biometric tracking system. The photograph also challenges notions of the instrumentalization of these surveillance mechanisms, which, as the photograph depicts, are not always dependent on non-human actors but also actual people. Ralph Hajjir, the sales manager whose Belgian company Semlex is responsible for implementing the recently-introduced biometric tracking system in Mozambique expressed and reinforced stereotypes regarding technology’s use in Africa. In an e-mail correspondence dated December 2014, Hajjar responded to my query about what his company sees as Africa’s demand for its services by stating:

[There] is a very important impact with the introduction of biometrics. Indeed, we caught many false ids and we improve the trust of the institutions such as banks or neighbor[ing] countries in those documents. Also you must understand that public records in Africa in general [are] really poor. So the official must rely [on] the final document because they have no access to information (i.e., civil registry, deeds and so on) (Hajjar, E-mail Correspondence, 2014).

It is important to understand the historical precedence for the biometric system (alluded to in Figure 1 by the presence of state officials in a living room and the presence of notebooks, pens, and a gun) because such a viewpoint highlights the histories at play in 2010 that are connected to 1983. Furthermore, reading the biometric as an extension of longer histories of surveillance and photographic production highlights the wide-ranging technologies that unfold around photography’s use, sometimes challenging popular and scholarly understandings of what is meant by photography.

If we begin with when the photograph in question was digitally reproduced, an interesting historical parallel and context emerges alongside the introduction of the biometric. Although steps had been taken to obtain the technology for implementing the biometric system in 2007, the government in Mozambique formally introduced it in 2010. Around the same time, Colin Darch, a historian and activist who lived in Mozambique during the 1980s, designed and launched the website Mozambique History (http://www.mozambiquehistory.net/). The photograph (Figure 1) is located under the tab “Operation Production” and included alongside the photograph are newspaper articles, magazine features, and opinion pieces Operation Production published in Mozambique from 1983 to 1993. Reading the textual in relation to the visual (such as Figure 1) highlights that in 1983 there was great public support, even a sense of urgency, that accompanied the introduction of new forms of identity documents. In contrast, in 2010, great public uproar greeted the introduction of the biometric. Interviews that I conducted from 2010 to 2011 with photographers based in studios revealed a longstanding and implicit relationship that photographers in commercial studios had with the government to photograph and print the pictures required for obtaining state-issued identity documents. The introduction of the biometric system in 2010 meant that the government no longer required the services of these photographers. It placed a strain on a popular and political relationship to technology and imparted new meaning and significance to knowledge of the past. At issue with the introduction of the biometric in Mozambique is a dispute over the past, which shifts the need away from explaining the public uproar over the biometric in relation to immediate concerns over costs and government impropriety. Of greater importance is to think through how photography and its use allowed for such a relationship between government and studio photographers to exist and to remain implicit for so long. What were the implications that this knowledge (when made public) had within the contours of contemporary Mozambique? To extend this point further, Figure 1 is significant because it demonstrates how photographs were used to identify people for Operation Production and the various actors that were on hand to verify and process the information presumably gathered from the photograph. Thus, the scene presented before the camera is the result of the presence or absence of identity documents, which depended on passport-sized photographs produced by studio-based photographers whose work the biometric system is eliminating.

To recap, the aim of Operation Production was to identify and relocate “unemployed” and “unproductive” populations who were overcrowding Mozambique’s urban cities. Introduced in June 1983, the program happened in two phases. First, individuals volunteered themselves for forced removal. In the second phase, occupants of urban centers were required to carry a series of identity documents that confirmed that they had a reason to be in a particular city, because they worked and/or lived in a particular place. State authorities reserved the right to see and question these documents. So, if we return to the opening photograph (Figure 1), there is a type of visibility that is not dependent on the existence of this actual print (and in turn not visible to the actual camera) but instead on what documents the individual (off center) pulls out of the pouch. Further complicating this largely visual space that emerged through the possibility of document verification was the reality that Operation Production relied on state officials being able to identify people for forced removal not based on the presence of documents but instead on the absence of documents (or irregularities within presented documents). So, another layer of visibility emerges when efforts by photographers resulted in the use of cameras, and sometimes pictures like the one under analysis here, to document Operation Production. Nevertheless, state authorities in Mozambique could neither ensure that photography studios had the supplies needed to provide headshots for the required documents nor provide themselves sufficient personnel and equipment to print needed documents. Additionally, categories like resident and worker that identity documents were intended to reveal and enforce did not always translate to the social conditions in Mozambique. For example, people may have “worked” as either street vendors or domestic workers but they did not have specific employers that entitled them to worker cards. Therefore, within the opening picture, a range of creative modifications, adaptations, and innovations are taking place around and through the use of photography that are sometimes not visible to the camera lens—a type of invisibility with its own political ramifications.

I would like to take a moment to reflect on how it is that we know what we know about Figure 1 and what photography, specifically the visual object, plays in constructing this knowledge. On the one hand, accompanying the republication of the print are newspaper articles and magazine features, which include information about government measures to administer Operation Production in addition to popular responses to such enforcement. On the other hand, these contextualizing materials also reveal something about the role of written text and the act of seeing in apprehending men through the visual forms and spaces of “visibility” and “invisibility” that sometimes accompanied photography. During Operation Production, the state-run newspaper, Noticias, rarely included photographs about Operation Production. Instead it used a daily column to respond to readers’ confusion over the program and to announce state authorities changes in the program. For example, the daily column included information about how to respond when businesses refuse service if a customer does not have the proper documentation and notified readers of the difference between evacuation centers and verification posts. In an article published July 7, 1983 in the state-run Noticias titled “Operation Production: Visits of Control to the Verification Posts,” government officials were quoted as saying that brigades of identification, which consisted of military elements (like the soldier pictured), members of the housing block, and local political officials, were to enter people’s homes with meticulousness and respect. And when we return back to the photograph with such information not only is the presence of the man in fatigues striking but so too are the men sitting at the table with their pens and notebooks. As an aside, while text proved important for the state to speak to, and often justify, certain actions (such as home entry), pictures of the military (like Figure 1) raised certain legal issues that drew the state into discussions over the legality of its actions and policing. While photography was responsible for drawing the state into such debates it was not necessarily the most adequate mode for state response.

From 1983 onwards, news publications in Mozambique created a public space (largely through writing) to talk about Operation Production. In turn, the press as a historical source also illuminates the relationship between text and image and the ways the public attempted to apprehend the photograph and assign meanings to it. The ID photograph took on added importance within Operation Production, which required three forms of identification. Colin Darch, who founded the website that I located the photograph under analysis, explained that state officials sometimes placed the photograph next to a person’s face. This was a practice that he claimed officials in Mozambique had learned through the nation’s international cooperation with the German Democratic Republic. However, as Figure 1 illustrates, there were also other forms of data in-take and documentation (such as writing down information notated on presented documentation) that were happening around and with the photograph. Darch himself remembers presenting his identity documents to officials in Mozambique during the 1980s. He recalled that the official refused to honor his documents because the stamp was not on top of the signature but instead besides the signature. Officials often challenged the veracity of the photograph and focused on the misplacement of stances and certain paperwork. In part, government efforts to identify subjects for OP through the presence and/or absence of the headshot determined what photographers photographed and what readers encountered within the press.

Embedded within Figure 1 are multiple, sometimes inter-related and at other times inter-dependent, layers of visibility and invisibility. These layers of visibility and invisibility reveal themselves and are at work through visual, textual, and oral mechanisms. Just as the state used the absence of identity documents to identify or make visible subjects for its social-development programs another invisibility was being created despite the presence and verification of a photographic print. These questions of visibility and invisibility confronted people living during Operation Production in ways that only the passage of time (and not the camera) could apprehend. The biometric tracking system is not new to Mozambique. In fact, less technologically savvy modes of surveillance existed earlier. But, what the biometric tracking system and the debates that unfold around it do is give new meaning to popular knowledge of Mozambique’s historical past and the ways in which photography filters this historical past into the present.

Suggested Readings

José Eduardo Agualusa, The Book of Chameleons: A Novel (New York: Simon & Shuster, 2007).

Ariella Azoulay, Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography (New York: Verso, 2012).

Heike Behrend, Contesting Visibility: Photographic Practices on the East African Coast (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2013).

Clapperton Chankanetsa Mavhunga, Transient Workspaces: Technologies of Everyday Innovation in Zimbabwe (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2014).

Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine (Bloomington: University of Indian Press, 1994).